The COVID-19 pandemic has sounded alarms about The American Way. In this nation historically resistant to equity, social justice is finally an emergency and a moral imperative. Every industry is reckoning with its baked-in inequities. The restaurant and food industry is no exception.

That’s why COOK Alliance lobbies for regulatory change on behalf of home cooks in California and beyond. The organization works with existing informal, home-based food businesses and provides support for the challenges they face.

Creating Opportunities, Opening Kitchens, known as COOK Alliance, is based in Oakland, CA. The organization was spun from Josephine, a private club formed by Matt Jorgensen and Charley Wang in 2014.

Jorgensen says informal food sales happen all the time in private cheffing and catering, and sometimes it’s what cooks do just to make ends meet. Josephine was named after a mother in the community who modeled sharing love through cooking, and Jorgensen says the club was an embodiment of the home cooking movement. It was “that feeling when you’re sitting in someone’s home, eating something they’ve made for you — [without] all the layers of political argument and complexity,” he says. Until it disbanded under regulatory pressure in 2018, Josephine provided a simple way for home cooks to sell food to one another, to neighbors, and to other people they knew.

Existing Cottage Foods regulation hadn’t gone far enough to meet the practical needs of home cooks, and didn’t offer latitude in the types of foods that could be sold, driving existing home-cooking businesses further underground, into an almost invisible marketplace.

“There was something lost in American cities like Oakland where this wasn’t allowed to be out there, in the open,” says Jorgensen.

Over the years, through Josephine and now COOK Alliance, Jorgensen and Wang have worked with thousands of home cooks. “Pillars of the community in their own right. It’s their labor of love, their side hustle, maybe it was something they did after church for the community,” says Jorgensen, “but by and large, it’s folks that have been excluded from the good opportunities in the regulated food world, [left to sink or swim] in the informal food world instead.”

Generally, these aren’t people that would have culinary school certifications or even experience working in a restaurant kitchen. An outlier, says Jorgensen, is “the trio of laid-off [cooks] from a Michelin-starred restaurant in Oakland, [who called] themselves the Broke Ass Cooks, but they were shut down.”

“Pillars of the community in their own right. It’s their labor of love, their side hustle, maybe it was something they did after church for the community, but by and large, it’s folks that have been excluded from the good opportunities in the regulated food world, [left to sink or swim] in the informal food world instead.”

MATT JORGENSEN

The Story of “Broke Ass Cooks”

“For about 10 years, Keone and I had worked together at Nine-Ten [in San Diego’s La Jolla district], then at Kobe in Oakland,” says Bilal Ali, one of the founders of Broke Ass Cooks. “That’s where we met Hoang, and all became roommates.” And eventually, they became home-cooking business partners, too.

When the pandemic hit, and they were let go from their restaurant jobs, Ali, with Keone Koki and Hoang Le, kicked off Broke Ass Cooks, cooking and selling foods of their cultures with tastes of Eritrea, Vietnam, Japan, and Peru.

Ali says, after having worked for people well-known in the Bay Area food scene, the trio had loyal patrons with significant social media followings. BAC was transparent with customers about the state of the restaurant industry, and how and why they started the business.

“Our story kind of resonated with people, and the community came together around us. We had a tent set up in front of our house. We were selling out in 30 minutes. We were doing extremely well,” says Ali. Less than two months later, he says, health regulators sent a short letter by mail detailing the misdemeanor nature of their operation, “and that was it.” The business was forced shut. The regulator’s letter had even been copied to their landlord, whom Ali says was gracious about the whole thing.

BAC was planning to go deeper in exploration of Eritrean and Vietnamese foods to honor the cultural aspects of their venture. “That meant something to all of us,” he says. It’s a beautiful vision and a goal that can be neither regulated nor shut down.

Ali and Koki now run Michoz out of the kitchen of The Hidden Cafe located in the middle of Strawberry Creek Park in Berkeley, where their creations are available for COVID-conscious curbside pick-up and outdoor dining.

“Our story kind of resonated with people, and the community came together around us. We had a tent set up in front of our house. We were selling out in 30 minutes. We were doing extremely well.” Less than two months later, health regulators sent a short letter by mail detailing the misdemeanor nature of their operation, “and that was it.” The business was forced shut.

BILAL ALI

The History of COOK Alliance

COOK Alliance works to help creative and scrappy ventures like Broke Ass Cooks flourish. Matt Jorgensen from COOK Alliance shares that “Charley [Wang] has a food justice bent, and me, I have more of the labor justice bent.” He had studied anti-capitalist organizing theory, and was excited by the potential for decentralization of work through the gig economy, as an attempt to do things better, he says. Now, in new ways, these are important parts of the equation in the efforts of COOK Alliance at the state and national levels.

Back when they were running Josephine, the co-founders had approached local regulators with good intentions and transparency about what the club offered: a fundamental way of getting to know a community and neighborhood, coupled with an overwhelming benefit of the home cook movement to low-income, marginalized communities, says Jorgensen.

“We were a little bit naïve at the time,” he says, “[thinking] that, by doing something like a private club, we could do it unregulated.” That’s when they learned this was a state-level issue, and “that was the origin of our organizing work around political change.” From that time to now, he says, their work has consisted primarily of storytelling, political organizing, coordinating with other advocates and like-minded organizations to write legislation, and just supporting cooks.

In the fall of 2019, “Our work culminated with the passing of two California state bills, AB626 and AB377 – the first laws to allow for permitted sales of home cooked foods in the United States,” the COOK Alliance timetable proudly documents. The landmark AB626, Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operations, or MEHKO, recognized the state’s food insecurity, informal food economies, and farm-to-table movement and, in light of those things, would expand the types of homemade foods permitted for public sale, finally creating hope for economic progress, especially in communities of color, through home cooking.

“A lot of [the work] has been putting together our list of asks, ensuring that cooks are at the table for negotiating and testimony each step of the way, and keeping the evolution of the bill true to the interests of the cooks it’s meant to serve,” says Jorgensen.

Prior to their work in Alameda County, which incorporates Oakland, COOK Alliance was integral in securing permits for home cooks in Riverside County, the first to adopt and implement the law, and the first to permit MEHKOs, beginning January 2020. According to Jorgensen, as of October 2020, there have been no public nuisance or public health complaints, and 80% of Riverside County’s MEHKO permit holders were from communities of color.

But social justice always comes at a price: In Riverside County, the MEHKO permit ranges from $651 to $1000 — “way higher than we would have liked,” says Jorgensen. In every county where AB626 is adopted, it brings a new revenue stream to the local government. COOK Alliance hopes to run campaigns for private funding and is looking to the County for ways to bring the cost down.

The ordinance has also passed in Lake County, where their six-month pilot kicks off this month. In Alameda County, adoption of the ordinance is still subject to a final vote. Assuming that goes well, “We’re told that they’ll be issuing permits in early 2021, and as soon as they green light, we’re ready to support cooks on the ground,” says Jorgensen.

Their model legislation is already helping other states create a legal pathway for home cooks. In Washington, a similar version of the bill is being workshopped, after which many home cooks across the state are likely to advocate for adoption and implementation in their own counties, just as cooks in California have done.

Lowering the Barrier to Entry

Eda Benjakul is an Emmy award-winning filmmaker, a former producer for ABC, a friend of COOK Alliance, and a daughter of restaurant operators.

Her interest in telling stories about food deserts and food insecurity in the US carried her into the same communities where COOK Alliance had long been hard at work, around the time that AB626 was coming up for a vote in Alameda County. Her recent short film Home Restaurant, Jorgensen writes, “brings us into the homes and kitchens of some of the first MEHKO operators in the US, beautifully telling their stories and illustrating the personal and community impact that MEHKOs have facilitated.”

The film won Best Short Documentary at the California International Short Film Festival. You can watch the film here.

“There are such financial barriers for people to bring their food and culture to their neighborhoods and communities, even [in] the rental space, alone,” says Benjakul. The licensing and start-up is simply cost-prohibitive for the average person. “You cannot get into a [traditional brick and mortar] restaurant business for less than $100K,” and she says this explains why there are so many franchises in Riverside County, and every large American city.

Ironically, an abundance of franchise operations reduces both food options and food quality, and that, Benjakul says, is the definition of a food desert. It’s the removal of choice, and that further justifies and illuminates the demand for broad adoption of AB626.

“There are such financial barriers for people to bring their food and culture to their neighborhoods and communities, even [in] the rental space, alone,” says Benjakul. The licensing and start-up is simply cost-prohibitive for the average person. “You cannot get into a [traditional brick and mortar] restaurant business for less than $100K,” and she says this explains why there are so many franchises in Riverside County, and every large American city.

EDA BENJAKUL

Benjakul grew up on the hyper-segregated, predominantly white northside of Chicago, a daughter of Thai immigrants. “We were the only non-white people in the neighborhood,” she says. Her parents opened one of the first Thai restaurants in the city when she was 12 years old. She says she remembers feeling unwelcome to live there, and that her parents were pushing their food on people. “It was embarrassing to me. I was like no one wants to eat this food, because it was new at that time.”

She knows now that her family’s restaurant and its food drew attention for its difference — not because it was new, but because it was ethnic. Interestingly, Benjakul says Chinese food had already been accepted — the prevailing Asian food in the white American ‘melting pot.’

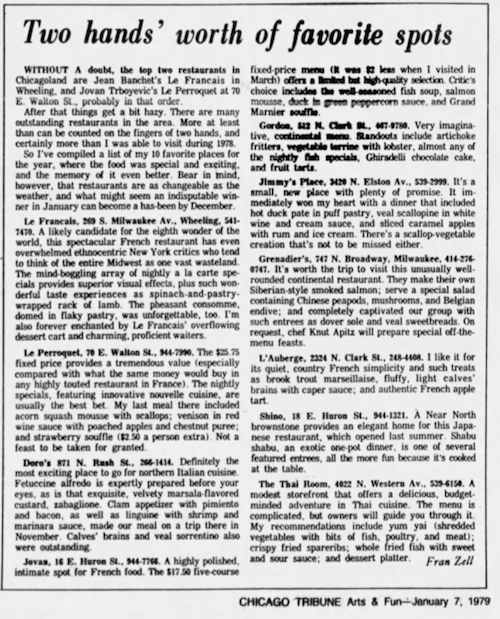

“But then the Chicago Tribune named ours one of the top ten restaurants in the city,” she says, setting their first generation Thai family-owned and operated restaurant alongside some of the best restaurants in the city.

“It was a validating experience, like we could be equal, on equal footing,” says Benjakul. This encouraged her young mind to question the status quo, and she says it was all because of food. “I think that food is an equalizer, and that it can open up conversation between people.”

In this time of COVID when many service industry jobs typically held by Black and Brown people have fallen away from the marketplace, the filmmaker says AB626 will provide a means by which home cooks can finally breathe and explore, and see what they can do, see what’s possible, legally. “Denise has a [permitted] home kitchen in Riverside County,” says Benjakul, “where she makes a gumbo with real crab legs. It’s beautiful food.” But more importantly, Denise’s MEHKO provides a perfect solution, enabling her to sell homemade food, earn money, and stay close to a family member in her care. The law actually facilitates and expands community service, she says.

Benjakul looks forward to more passages and implementations of AB626 in California, with permits issued in quick succession. Echoing this, Jorgensen says it’s past time that historically marginalized entrepreneurs feel the pride of business ownership.